This Article will explain why various subdivisions of Jews were created and how these function within the ‘umbrella’ of Judaism today.

All Jews share much in common including our culture and history. Over the last 4000 years or so of experience within many cultures, many traditions have evolved.

Up until about 200 years ago there was only one main form of Judaism- Orthodoxy.

Nowadays one can find subdivisions of the faith worldwide such as Haredi, Hassidic, Lubavitch (all ultra Orthodox), Conservative (also known as Masorti), Reform, Liberal/Progressive or even secular.

There is therefore no such thing as ‘One Jewish Way’ but many and various ‘Jewish Ways’.

Many Jewish families will have members belonging to different subdivisions.

For the purposes of this article, they will be separated into the two main divisions- Orthodox and Reform/Liberal. Please note however that there is a degree of difference and fluidity even within these groups.

Rationale

The traditional Orthodox view is that the Torah was revealed and literally dictated by God to Moses on Mount Sinai, ie: ‘The Revelation’. As such, it is to be taken word for word as the truth, followed to the letter and never questioned.

This includes all the various explanations and interpretations of the written law, passed down by word of mouth, known as the ‘Oral Law’.

However Biblical research and modern history has undermined many of the traditional Orthodox basic beliefs about Judaism by challenging the long held view that the whole Torah is to be taken literally.

Modern scholars argued that the Torah is ultimately the result of generations of human authorship. Therefore however holy and divinely inspired, it was still open to human inconsistency and error. Also history and religious development within the Bible itself had affected its relevance and credibility in the modern age.

These views effectively challenged the sanctity and authority of the Bible and questioned its position as the ultimate source for all subsequent Jewish legislation.

It also denied the notion that there has always been one unchanging form of Judaism that must continue to be upheld.

Therefore a radical re-evaluation of Jewish beliefs and practices was necessary to respond to such findings and constructive questioning and criticism of the Torah and Talmud was to be encouraged.

In practice this allows for fluidity and gradual change and interpretation of the written law appropriate to the situation, time and context.

Historical Background

Reform Judaism

The Jewish Reform Movement began in Germany at the beginning of the 19th Century when ‘reforms’ in services were introduced eg: prayers in the vernacular and shortening of services.

These reforms helped to improve the quality of Jewish rituals and made services more ‘attractive’ and relevant at a time when numbers were declining.

However until the 1930s only a handful of ‘reformed’ Synagogues existed.

In the UK, growing disillusionment with Orthodoxy led to the establishment of the Reform Movement in 1942 with the opening of West London Synagogue.

Eventually the different UK Reform Synagogues joined one umbrella movement known as the RSGB- the Reform Synagogues of Great Britain. Today there are 41 member Synagogues.

Liberal/Progressive Judaism

In 1902 the Jewish Religion Union was formed, led by Claude Montefiore and Lily Montagu. This was the beginning of the Liberal/Progressive Movement. It took further steps towards modernising Judaism. In 1911, it was formalised as the Liberal Jewish Movement with the opening of its first Synagogue in St John’s Wood, London. Today there are 38 Liberal/Progressive communities in the UK.

Both the Reform and Liberal/Progressive Movements play down elements such as the expectation of a Messiah, the resurrection of the dead, the re- building of the Temple in Jerusalem and a desire to return to the Holy Land.

Many Jews believe in both the value of tradition and the need for change and these Movements allow for a constantly evolving way of Jewish life which leaves one free to express one’s individual religious freedom.

It is important to emphasise that whether Jews consider themselves to be Haredi, Orthodox, Reform, Liberal/Progressive or indeed secular, they all share a common culture, history and belief.

All denominations of Judaism adhere to common concepts such as being just, speaking the truth, promoting peace, treating others with kindness, being humble, refraining from negative speech, being charitable and looking after God’s world as its guardians.

Examples of Differences in Practices

The fundamental theological difference between Orthodoxy and Progressive Judaism has resulted in some major differences in Jewish practices.

Some examples are below:

Jewish Identity

Orthodox

A Jew is born from a Jewish mother or a mother who is a convert to Judaism as recognised by the appropriate Orthodox authorities. (It is visibly obvious who one’s mother is).

Progressive

A Jew is a child of a Jewish mother or father or a convert through any rabbinic authority.

Some communities will expect a non-Jewish mother to either convert or undergo instruction in Judaism and to actively practice the faith.

Equality

Orthodox

Men and women have distinct religious roles. Men are obligated to pray and read from the Torah.

Women are responsible for the home and education of the young children. Only boys can be Bar Mitzvah. Girls may have a Bat Chayil. (See Bar/Bat Mitzvah)

Progressive

Equality in all practices for example, sitting together in Synagogue, joining in the prayers, reading from the Torah and women becoming Rabbis.

They also share the same responsibilities within the community, in public or at home.

Following All The Commandments

Orthodox

Jewish Law, Halacha, is based around the 613 ethical and ritual commandments in the Torah. These must be strictly observed.

Progressive

The commandments were a human attempt to interpret God’s desire for us to lead a holy and honourable life. Personal observance of the commandments is a matter of choice as long as it is guided by education and integrity, especially as some commandments are no longer appropriate.

Observance of Shabbat

Orthodox

In the Torah there are 39 types of work forbidden on Shabbat. For example Orthodox Jews do not drive, use electricity, handle money or carry anything.

Progressive

Jews will keep the ethos of Shabbat but will use the conveniences of the modern age to enhance it- for example, driving to Synagogue, listening to Jewish music on the IPod.

Prayer

Orthodox

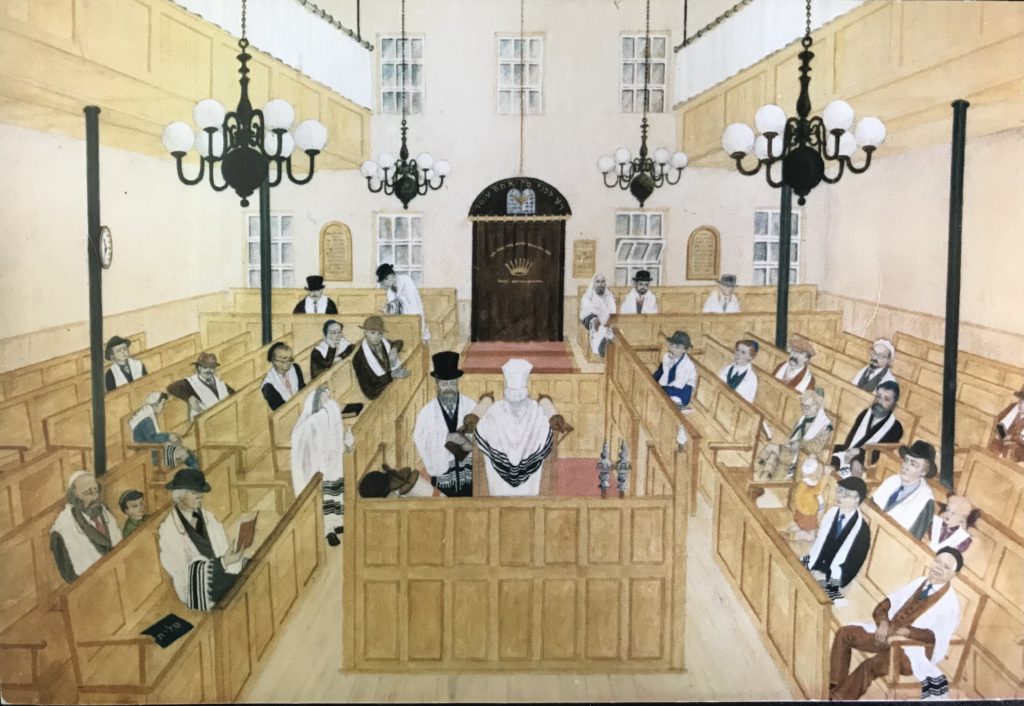

Men are obligated to pray 3 times a day, preferably with their community. There must be a minimum of ten Jewish men present in the Synagogue, known as a minyan.

Men and women sit separately. Women are not obligated to pray and therefore have a secondary place in the Synagogue. This may be at the back behind a partition, to one side or upstairs in the gallery.

Services are daily and conducted in Hebrew which is read rapidly. Some of the prayers are silent and followed individually rather than read together. The whole week’s Torah portion is read. Services are lengthy- the Shabbat service may last 3 hours or more.

There is no organ or choir but there may be a Cantor (Chazan) who will chant the prayers.

Members may ‘Daven’ – rock backwards and forwards as they pray.

Progressive

Private and regular prayer is encouraged along with communal prayer. Services are held at Shabbat and festivals. Men and women sit together in Synagogue. The Rabbi or a lay reader of either sex may lead the service which will be conducted both in Hebrew and English. The prayers are read together at a moderate pace. Services have been revised and modernised to be simpler and reduce repetition. A shorter Torah portion is read on Shabbat and the service will last for an hour and a half to two hours.

There is often an organ and a choir to enhance services.

Appearance

Orthodox

It is customary for Orthodox men and boys to wear their Kippot both at home and in public (see How and Why Jews Pray).

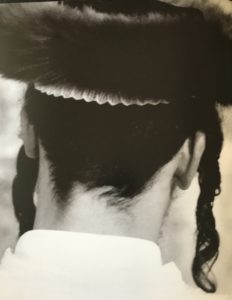

Ultra Orthodox (Haredi) Jews are very recognisable by their distinctive black garments which are worn for reasons of tradition, ritual and modesty. The Kippah will be under a black hat or a ‘shtreimel’, a furry hat.

Hasidic Jews (a branch of Haredi Judaism) will often wear long black suits reminiscent of the suits worn by Polish Jews in the 18th Century where the Hasidic movement began.

It is also customary for this group to wear beards as a sign of piety. This practice derives from Leviticus in the Torah which states ‘You shall not shave the corners of your head round or destroy the corners of your beard’. In other words, the use of any cutting or slicing objects on the face is forbidden. Therefore this practice also extends to the sidelocks, known as ‘Payot’, which are often curled and sometimes tucked discreetly behind the ears.

Hasidic men will often wear a ‘Tallit Katan’ literally ‘small Tallit’ under their suits, also known as ‘Tzizit’. This is a poncho style garment made of white wool or cotton with the Tzizit in each corner and/or knotted in sections.

Orthodox women dress with modesty and will not expose their bodies. They also do not show their hair after marriage. Instead they will cover it completely with a wig (Sheital in Yiddish) or a headscarf. This is to show propriety and marital status. It became a tradition in the 15th Century and has been adhered to in Orthodox Judaism ever since.

The above customs will vary according to the degree of Orthodoxy followed.

Progressive

There are no religious requirements as regard dress and appearance although it is preferable to dress in a respectful way for synagogue. Women and girls may wear Prayer Clothes.

Food

Orthodox

The food rules- Kashrut – are kept strictly both within the home and wider community.

Biblical rules permit and prohibit certain foods as well as stipulate methods of killing and preparation. According to later Rabbinical laws, dairy foods are not mixed at one meal or sometimes even on the same day!

Progressive

Following the food rules is a matter of personal choice and integrity. Many Progressive Jews keep the Biblical laws as a matter of tradition and an accepted part of Jewish life and /or as a valuable exercise in self-discipline.

Some follow Kashrut because they view its religious and ethical significance only in so far as its health considerations because we have a duty to keep ourselves fit and well. After all, our bodies are given to us in trust by God. At the same time we also have a duty not to inflict avoidable suffering on animals.

Festivals

Orthodox

As with Shabbat, rules about not working are strictly followed. Outside Israel, an extra day is kept for each festival to allow for uncertainty regarding observing the correct day. There are a variety of extra fast (non-eating) days which generally relate to the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem.

Progressive

As with other situations, observance depends on the individual but stress is put on the meaning and modern relevance of the festival. This often translates into action. For example, protesting against slavery at Passover, helping with homelessness at Sukkot and planting trees to demonstrate our awareness of ecology at T’u B’Shevat.

As in Israel, festivals are only observed for one day and those associated with the destruction of the Temple are omitted.

Death

Orthodox

For over 2000 years, Judaism has believed in some sort of life after death. However the emphasis has always been on living one’s life to the best of our ability as regulated by the rules in the Torah.

The body contains the spirit- ‘holy spark of life’ and on death it returns to God who made it. The body returns to dust and must be treated with respect. Hence it must be buried and not cremated.

There are certain practices associated with burial and mourning. (See Life Cycle Events).

Progressive

In Biblical times there was no real idea of life after death. This came later as a way to try and understand and explain ‘why the good die young’. The idea that perhaps they were so good that God required them now in ‘the life to come’ and they would ‘live forever in happiness’.

(I personally have always found this thought of much comfort, having lost my dear father when I was 18).

Individuals can decide for themselves what they believe.

Cremation is acceptable although echoes of the Holocaust may affect this decision.

The Future

Orthodox

Belief is in a personal Messiah who will be a direct descendant of King David and who will usher in an age of peace. He will restore the Temple in Jerusalem and gather Jews together from the Diaspora into Israel. The restored Kingdom of Israel will live in peace with all nations.

Progressive

The belief is for a Messianic time rather than a person. The Synagogue has taken the place of the Temple and therefore its restoration is not a priority.

Every individual should work towards a Messianic time when all peoples will live in peace and harmony.