In practical terms because God is the cornerstone of our faith, we bring Him into every aspect of our lives. (See Jewish Concept of God).

This could be through prayer, ritual, worship and also through the symbolism that we use around us in our homes, in our synagogues and even with our clothes. (See Symbols of Judaism).

In this article I am going to look at the concept of prayer, its importance within Judaism and the practices associated with it. For the purpose of the article I am going to refer to God in the masculine. This is not because I necessary think of God as a person – I regard Him more as a Spirit or Force but I find it easier to portray Him as a caring Father. It’s more personal that way.

What is Prayer

When we pray we are talking to and spending time with God which builds our relationship with Him.

When we pray, our thoughts and feelings can reach out to God and we can feel closer to Him.

The most important thing is to remember to pray with total concentration on what we are saying and thinking – there must be nothing else in our heads like what’s for tea or where am I going later? We must be ‘mindful’ or ‘in the moment’ and totally mean what we are saying.

In this way, we can find the spiritual part of ourselves – it’s almost like we go to a special place in our heads- a different place from our everyday thoughts and worries.

If we pray often, like most things, we get better at it.

Why Jews Pray

We pray to remember and express our beliefs. We remember that God is a source of strength and support in happy and sad times. He has always been there for us and always will be.

Jews pray to obey God’s commandments so that we can do good things like be kind to each other and to help make the world a better place for all of us.

Praying is one of the most important parts of our worship.

Orthodox Jews pray three times a day – in the morning, the afternoon and the evening. They have services in synagogue every morning and on Festivals.

Reform and Liberal Jews can pray anytime. The synagogue services are held on Shabbat – Friday evenings and Saturday mornings and also at Festival times.

(See also Subdivisions within Judaism).

Types of Jewish Prayer

We have three types of prayer- 1) prayers which praise God and all that He has done, for example, giving us the Torah.

2) prayers which give thanks for the good things in our lives, eg: the Shabbat blessing over wine, which thanks God for ‘creating the fruit of the vine’ and the blessing over the Challah bread, which thanks God for ‘causing food to come forth out of the earth’.

3) prayers that ask for things, for example, happiness and good health for us and our families. And many prayers for peace, not just for ourselves and the Jewish people but for all people. We also ask Him to help world leaders to make good decisions.

Indeed there are prayers for most situations, however mundane, for example over washing one’s hands, eating a biscuit, smelling perfume, seeing a rainbow and even, in a pandemic, putting on a mask! Orthodox Jews will always start the day with a prayer called ‘Modeh Ani’ which says ‘ Thank You Living and Eternal King for mercifully restoring my soul within me. Great is Your trust’.

All these prayers remind us that God is involved in everything we do in our daily lives.

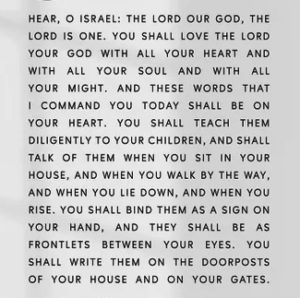

For all groups however there is one prayer which is the most important of all. This is called the Shema (pronounced Sh’MA – emphasis on last syllable).

Shema means ‘hear’ or ‘listen’ and the first couple of lines encapsulate the whole ethos of Judaism- ‘Hear O Israel the Lord is our God, the Lord is One. And you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, all your soul and all your might.’

It then tells us to say these words throughout the day and teach it to our children.

Finally it tells us to write these words on the doorposts of our house. This is why Jewish homes have a Mezzuzah on the front door and often inside too on every door except the bathroom. (It is thought to be inappropriate for it to be near people who are undressed). We touch or kiss the Mezzuzah when we go in and out of the house which reminds us to say the Shema. (See The Jewish Home).

How Jews Pray

We can pray on our own anywhere or we can pray together more formally with our friends, families and other members of the Jewish community in a Synagogue. (See The Synagogue).

When Jews pray, we don’t fold our hands together and we don’t kneel.

In synagogue we stand up for important prayers like the Shema and the Amidah (literally ‘standing prayer’).

Orthodox Jews may ‘Daven’ (sway) or bow their heads. They often pray individually and chant the prayers following a Cantor (Chazan).

Progressive Jews follow the Rabbi’s lead. Prayers may be spoken, said silently or sung, often with a choir.

The Prayer Clothes

Jewish men and boys wear special clothes for prayer. Nowadays in more modern Jewish groups, some women and girls wear them too – (see Subdivisions within Judaism)

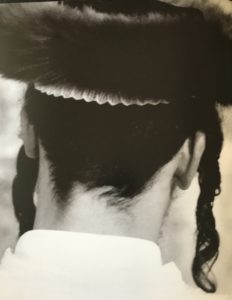

The Kippah (plural Kippot)

This is a skull cap, also known as the Yarmulke or Koppel. It is the prayer cap, worn to respect God and to remember that He is above you. Traditionally they have only been worn by males but nowadays many Progressive Jewish women wear them too.

Kippot can be any colour, fabric and design. They are often made of a sumptuous fabric such as velvet or satin and decorated with Jewish symbols. Children often wear fun ones and you can even get ones for babies!

Black Kippot are usually worn for funerals and white ones at weddings and on High Holy Days – white being the colour of purity and holiness.

They are worn both at home and in the synagogue. Progressive Jews tend to wear them only for prayer but Orthodox men and boys may wear them all day- the Ultra Orthodox, under large black hats.

Interestingly the wearing of Kippot is not a requirement from a commandment in the Torah but from a story in the Talmud.

The Tzizit and Tallit

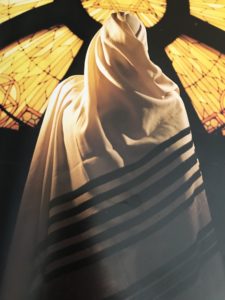

The meaning of the word Tallit is literally ‘cloak or sheet’ and refers to a fringed prayer shawl or scarf worn during prayer by Jewish males and in Progressive Judaism, some Jewish females.

Its origin is found in the Torah where it is commanded by God to wear ‘Tzitzit’ -knotted tassels on each corner of a garment. These symbolise that God is in each corner of the earth ie: everywhere.

This commandment is followed in a literal way by Hasidic men who often wear a ‘Tallit Katan’ literally ‘small Tallit’ under their suits, also known as ‘Tzizit’. This is a poncho style garment made of white wool or cotton with the Tzizit in each corner and/or knotted in sections.

The ‘Tallit Gadol’ literally ‘large Tallit’ is the outer shawl worn over the shoulders usually made from wool, linen or silk. It will have both Tzizit on all the corners and also fringing along the short sides.

In the Shema, it tells us that the fringes are a reminder to follow all God’s commandments.

The Tallit are usually white or cream with blue or black stripes. The Shema stipulates that there must be a blue thread in the Tallit. (The colour blue reminds us of God in Heaven above the blue sky – see Symbols of Judaism).

The Tallit is often embroidered with symbols such as the Star of David and the Ten Commandments. Around the neck are also embroidered the words of the prayer one says as one puts it on – ‘We praise You, Lord Our God, King of the Universe, who has sanctified us by His Commandments and commanded us to wrap ourselves up in tassels’.

This prayer is usually recited with the Tallit worn over the head. The Tallit is then placed over the shoulders. This ‘wrapping up’ also serves to focus one’s mind towards prayer – all distractions are literally shut out for a few seconds.

Nowadays more modern and colourful designs are available, particularly for Progressive women.

It is traditional to give children their adult Tallit and often beautiful silver Tallit clips on the occasion of their Bar/Bat Mitzvah to symbolise becoming a Jewish adult.

Every family will have beautiful Tallit bags to keep their prayer clothes in.

The Tefillin

Tefillin are worn by Orthodox adult men (and boys after their Bar Mitzvah) for weekday morning prayers except on Shabbat and Festivals.

They are literally ‘prayer boxes’ or phylacteries- from the word ‘Tefillah’ meaning prayer. The Tefillin in the photo on the right belonged to my Grandpa, Moses Montefiore Cohen.

Tefillin are two small leather cubed boxes containing tiny parchment pieces on which are handwritten references to texts from Exodus and Deuteronomy in the Torah. The Tefillin are worn because of the directive in the Shema which says ‘All these words I command you this day shall be on your heart……You shall wear them as a sign on your hand and as a reminder between your eyes.’ (See Shema above).

Therefore one Tefillin box is identified as ‘Shel Yad – for the hand or arm’ and the other ‘Shel Rosh’ for the head. They both have leather straps. The ‘Shel Yad’ is wrapped 7 or 8 times around the left arm. This is because it is nearest the heart and generally considered to be the weaker arm and so ‘needs’ God’s words and strength. For the same reason, a left handed person will wear it on their right arm.

The other Tefillin, ‘Shel Rosh’ is placed on the forehead between the eyes and tied behind the head.

Families will have a separate decorated bag for their Tefillin.

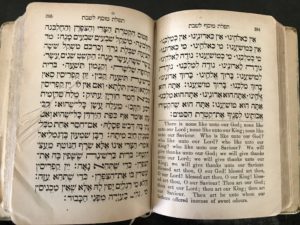

The Prayer Book

The prayer book is called a Siddur. This word comes from the Hebrew word meaning ‘order’. In Orthodox Judaism these may all be in Hebrew but more Progressive Siddurim (plural) will contain both Hebrew and the vernacular.( See Subdivisions within Judaism).

These books are divided up into services for different occasions such as Shabbat services, festival services and daily prayer. These services contain a set order of prayers. (See Order of Shabbat Morning Service for an example).

The Progressive Siddur will also feature meditations, songs, Psalms, poetry and themed sections. There will also be prayers for special occasions such as births, conversion to Judaism, Bar/Bat Mitzvot (plural), weddings etc. as well as writings of Jewish philosophers and scholars across the ages.

Just like Hebrew itself, the Siddur is read from right to left.

There are separate Siddurim for certain occasions for example, the Machzor for High Holy Day services, a prayer book for use at home – see L’Chaim! meaning ‘To Life!’ below and the Haggadah prayer book for the festival of Passover.

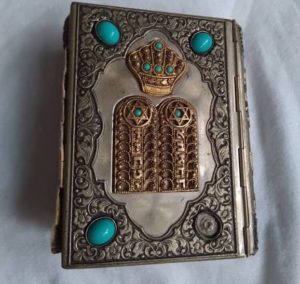

Some Siddurim are incredibly ornate!

There are also prayer books designed specifically for families and children to use.

Conclusion

Prayer is an integral part of Judaism. It serves to enrich our lives and gives us comfort and stability.

It connects us to our past and joins us together with our fellow Jews around the world.

It helps us to celebrate and be empathic with others.

Prayer helps us develop a sense of the sacred but ultimately its purpose is to serve God and make ourselves more ‘Godlike’ by following His Commandments and His wishes as stipulated in His Covenant.