As evidenced by many different world religions, it is important to acknowledge key milestones in life. Such ceremonies are known as ‘Rites of Passage’.

In Jewish tradition, all life cycle events have rituals which mark these.

In this section we will look at Birth Ceremonies and those of Marriage, Divorce and Death.

(Bar/Bat Mitzvah and Kabbalat Torah are explored in other Articles.)

Background

Life cycle ceremonies happen at moments of change such as the arrival of a new child, a wedding or death. They are important not just to the family concerned but also to the wider Jewish community. This sharing of joy or sorrow traditionally brings a sense of closeness and greater cohesion.

Birth

It is a well known fact that the unit around which Judaism centres is the family. Judaism teaches that having children is a ‘Mitzvah’, a Blessing. Of course, not all couples can have children but it is felt that those that can, should. It is then the responsibility of the parents to make sure the children are brought up in a practising Jewish family.

There are some differences in defining the ‘identity’ of a Jewish baby in the different branches of Judaism.(see Subdivisions within Judaism).

In Orthodox groups, a child is recognised as Jewish if the mother is Jewish or is a convert as recognised by the appropriate Orthodox authorities.

In Progressive Judaism a Jewish child is that born of a Jewish mother ( or father in Liberal Judaism) or a convert through any rabbinic authority.

Some Progressive communities will expect a non-Jewish mother to either convert or undergo instruction in Judaism and certainly to actively practice the faith.

Boys

Traditionally Jewish baby boys will undergo circumcision. This is known as Brit Milah – literally The Covenant of Circumcision. Amongst Jews, it is known as The Bris. (Yiddish).

This ceremony is the oldest unchanged Jewish ritual. It dates from the original Covenant between God and Abraham. Abraham was commanded to circumcise himself and all his male descendants as a sign of his commitment to God. (See Genesis Chapter 17 verses 10-14). It is an external sign of this Covenant demonstrating that the child will be brought up as a faithful member of the Jewish faith.

The circumcision is usually performed at home on the eighth day of life, unless the baby is not strong enough, in which case it will be delayed. The foreskin on the penis is removed by a specially trained professional called a Mohel. The child is then named at the Baby Blessing. (See below.)

The whole group present will then pray that the child will faithfully follow the laws of the Torah and be a good person. Wine is passed around and this is then followed by a party.

Others (myself included) may prefer a more low key occasion, using a doctor trained in circumcision and conducting their own prayers or inviting a Rabbi to the house.

It has been suggested that circumcision is an appropriate sign of a Jew’s loyalty because it takes place on the organ from where future generations are created. Some also consider a foreskin to be unhygienic.

It is a fair point that people may question whether this ceremony is barbaric in the modern age.

However it has been explained that it is a fundamental part of the Jewish identity and commitment. Indeed, should circumcision be needed later on in life for health reasons, it is far better to do it at a very early age instead of in adulthood. Of course, it is a requirement of adult males who wish to convert.

Girls

Girls will be named at the Baby Blessing.

The Baby Blessing

This is a ceremony in Synagogue in front of the family and community. Its purpose is to recognise and celebrate the arrival of the child and to welcome him or her into the family and the wider circle of friends and community.

The mother will offer thanksgiving for coming through childbirth safely. The baby will then be given its Hebrew name. This will be a first name, usually one found in the Torah or of a relative, living or deceased. The first name will followed by the words ‘son or daughter of’ then the father’s first name and in Progressive Judaism, the mother’s as well. For example my Hebrew name is ‘ Yehudit Bat Zvi v’Haya’ which means ‘Little Jewish girl, daughter of Henry and Sylvia’.

Weddings

Judaism has always emphasised the sanctity of marriage. It offers love and companionship and creates a Jewish home- the ideal Jewish environment for bringing up children.

The home is regarded as a small ‘sanctuary’- a place of holiness where Judaism is practised and passed on from generation to generation.

The Wedding Ceremony

It is only possible to hold a Jewish Wedding ceremony if both parties are Jewish.

There are some differences in practice between Orthodox and Progressive communities but for the sake of simplicity I have outlined the main elements of the traditional Orthodox ceremony.(See Subdivisions within Judaism).

On the Shabbat prior to the wedding, an Aufruf ceremony may be performed. This is when the groom (and also the bride in Progressive synagogues) is called up to read the Torah Blessings – the Aliyah. There may also be a special Kiddish for the couple afterwards.

Weddings are generally held on a Sunday but can take place on any day except Shabbat (Saturday) or festivals.

The wedding itself usually takes place in the synagogue but can be held anywhere- the premises does not need to be licensed – all that is needed is a Chuppah (see below). Anyone can act as the celebrant although the ceremony must be held under the supervision of a Rabbi. In the UK, the civil and religious ceremony are usually combined; the synagogue having its own marriage registrar who ensures all the legal requirements are fulfilled.

It is customary in Orthodox weddings for the groom to perform Bedecken before the ceremony. This is literally a ‘veiling’ of the bride. This practice refers back to the Bible story when Jacob was deceived into marrying Leah instead of Rachel because her face was veiled. The bride will have her face uncovered, the groom can check he has the correct bride and then he places the veil over her face! The veil is also a symbol of modesty and it is usual for the bride to keep her veil on until the kiss at the end.

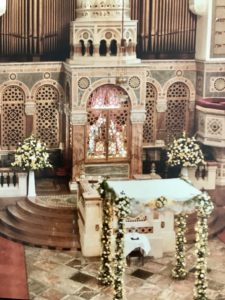

The couple will stand under the Chuppah which faces the Holy Ark. The Chuppah is a canopy made of silk or velvet or a Tallit, which lays across four self-supporting poles. This represents their future home and is often bedecked with flowers.

The bride stands under the Chuppah, dressed in the conventional white dress with her face covered by the veil. She will be to the right of the groom (if you’re facing the Chuppah) with the two sets of parents at each side and the Rabbi facing the couple.

In some ceremonies the bride will walk around the groom seven times as the Blessings are said, thereby symbolically creating a new family circle and demonstrating that the groom is the centre of her world. The number seven also represents the seven Blessings (see below) and the seven days of creation.

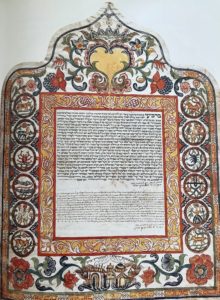

The service lasts between 20-30 minutes and incorporates the key elements of the Chuppah, the giving of wedding rings and the Ketubah. (Hebrew – written commitment). (See below).

Traditionally wedding bands are made of metal-gold, silver or platinum with no stones. During the exchange of rings the couple take turns to say “Behold you are married to me in holiness, according to the law of Moses and Israel.”

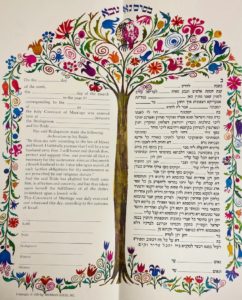

This is followed by the reading of the Ketubah in Hebrew and English. This is the ‘Marriage Contract’ signed by the couple and witnessed, prior to the service. The Ketubah, which is often beautifully decorated, used to be a legally-binding financial contract but nowadays is more of a promise of mutual love and care and the establishment of a Jewish home.

The couple will also receive the civil marriage certificate.

Then follows the recital of seven traditional Blessings. These include thanking God for creating wine, the world and its people and asking God to bring happiness to the couple.

They will then each sip the wine from the Kiddish Cup.

The last ritual is when the groom steps on a wrapped glass cup to smash it. This symbolises the fragility of marriage and that marriage has to be worked at. It is also a reminder of the destruction of the second Temple in Jerusalem. The joke is usually made that ‘this is the last time the groom will be putting his foot down!’.

Everyone will then shout Mazel Tov! ( Congratulations)

After the ceremony, some couples follow the tradition of spending at least 8 minutes together in seclusion, known as Yichud. This gives them some precious private time to reflect on the occasion and celebrate. Sometimes they may also share their first meal together as a married couple during this time.

The celebrations will continue with food, partying and dancing and at some point there will be Israeli music. The guests will lift the bride and groom high up on chairs and carry them around. (A very nerve-wracking experience!)

In Orthodox groups men and women will celebrate separated by a partition to preserve modesty.

In Progressive communities, same sex marriages are allowed. If a Jew marries a non-Jew, the Rabbi may conduct a service of blessing and celebration. Conversion to Judaism would be encouraged in which case a Jewish wedding service would be allowed.

Divorce

Sadly of course, not all marriages work out. Judaism has always recognised this and makes provision for divorce. In Orthodox Judaism a ‘Get’ or ‘Gett’ ( Bill of Divorce) is given by the husband to the wife. This enables the woman to remarry in an Orthodox Synagogue and any further children will be considered as Orthodox Jews. There can be problems with this when the husband refuses and the woman is then known as ‘ Agunah’ ( Chained). She is literally ‘anchored’ into her religious marriage and is unable to remarry within the Orthodox community. Any subsequent children would be considered illegitimate however it is usually possible for a religious Court to remedy this situation.

Although Progressive Judaism does not grant a religious divorce in the same way, the wife would be encouraged to receive a Get in case she wishes to remarry an Orthodox Jew. A secular decree nisi is accepted although if the couple wish to end their marriage as it began, a religious ceremony and ‘document of release’ can be arranged.

Death

Judaism is very clear that the human body is considered to be sacred and holy. The deceased body still retains its holiness therefore there are important rituals that should be followed.

The Orthodox view is that no non-Jew should touch the dead body of a Jew. Progressive Jews accept that sometimes this has to happen, for example in a hospital if the body has to be taken to another room.

Then Taharah (ritual purifying) takes place conducted by a specially trained member/s of the community, known as Chevra Kedusha. (Holy Society).

Men will prepare men and women will prepare women. The body is washed, the limbs straightened, the arms placed alongside the body (never crossed) and the mouth and eyes closed as a mark of respect. Many families dress their loved one in a special white shroud (a Kittel) or a somber suit or dress.

A Tallit (prayer shawl) is placed around the shoulders of a man with the Tzitzit ( fringing ) cut off. This shows that the person no longer has to follow the Torah commandments that the Tzizit symbolise.

There is then a tradition of ‘guarding’ the body by ‘watchers’ – usually close family or friends. As a mark of respect, the body will not be left alone nor is the coffin allowed to be left open as this is seen as disrespectful to the deceased. Embalming or any cosmetic process is strictly forbidden.

It is customary for the close family to sit on low stools for a week or even up to a month, mourning the death, known as ‘sitting Shiva’ (literally seven days).

This symbolises the feeling of being prostrate with grief, literally feeling low.

Men will often not shave for a month as an outward sign of mourning.

During this time a Yarzheit (memorial) candle is lit and prayers are said for the soul of the deceased.

It is a Mitzvah ( good deed) to visit mourners to comfort them and also bring food so they can focus on their grieving. It is customary for the community to hold formal ‘Prayers’ at the house of the deceased for one or two nights after the funeral. This allows those who can’t attend the funeral itself to show their respect and support.

The conventional way to greet members of the deceased’s family are the words ‘I wish you long life’. This represents the instinctive focus Jews have that despite the overwhelming grief, life carries on.

The Funeral

This must happen as soon as possible- preferably within 24 hours- although never on Shabbat or festivals. In reality they generally take place within two to three days to allow time for legal and practical reasons, such as travel arrangements to be made. Orthodox Jews will only bury their dead ie: return them to the earth (see below- Life after Death).

Progressive Jews allow cremation. Ashes can be buried with a headstone or placed in an urn in a Wall of Remembrance in a Jewish cemetery. Alternatively they can be scattered according to the wishes of the deceased.

Orthodox communities discourage women from attending the funeral- the rationale being that it’s the men who are obligated to pray and women can cause a distraction.

It is usual for mourners to dress appropriately and in dark clothes. Before the funeral, Orthodox relatives will make a symbolic cut of a few inches on part of their outer clothing as a sign of mourning. This is known as Keriah. Alternatively they will pin a torn black ribbon on their clothes. This is a striking expression of grief.

The Funeral service is short, consisting of a combination of prayers and appropriate Psalms.

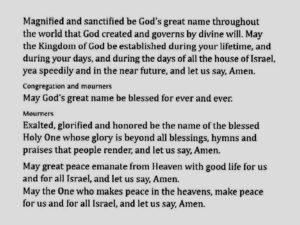

There will be eulogies for the deceased and the service concludes with reciting the mourners’ prayer- the Kaddish.

More prayers will be said at the graveside and mourners will traditionally assist with the initial filling in of the grave. (There will be sinks placed on site for hand washing.)

It is not customary to have music at Jewish funerals because music is generally associated with celebration and may distract the mourners. Flowers and wreaths are also not usually seen. This is because whilst flowers are a beautiful gift to the living, they mean nothing to the dead. Instead it is usual to place a stone on the grave. The body, like a flower, blossoms then fades away whereas the soul, like a solid stone, lives on forever.

A stone is a lasting presence of the deceased’s life and memory and a physical reminder that a loved one has visited.

This practice may originate from Biblical times when a small stone mound, a cairn, marked the location of the grave.

It may also hark back to the practice of leaving a note on the grave and putting a stone on it to keep it in place. Eventually the note would disintegrate but the stone would still remain.

The Stone Setting

This is a short service at the graveside to consecrate the headstone and may take place from three months after the death. In reality it can take up to a year to arrange the making of the headstone. It marks the end of the official period of mourning.

Yarzheit

On the anniversary of the death every year, the family will light a Yarzheit candle in the home. On the Shabbat nearest to the anniversary, the deceased’s name will be read out in Synagogue prior to the Kaddish.(Mourner’s Prayer).(See above).

Suicide

Orthodox Judaism sees suicide as a sin- only God should make the final judgment on life or death. Progressive Judaism takes a more pragmatic and sympathetic view. It sees it as akin to death caused by an illness. There are also mixed views on matyrdom. Some see this as the ultimate act of heroism; others that life, a gift from God, should be preserved at all costs.

Heaven and Hell

Unlike some religions, Judaism doesn’t have specific teachings about Heaven and Hell.

For a time, people believed in a place called ‘Sheol’ which was a dark place where the dead waited for eternity. Others thought that the righteous would go to Gan Eden – the Garden of Paradise and the wicked would go to Gehenna – Hell. Nowadays there is no recognised concept of Hell because Jews believe that the importance of life is how it is lived on earth. Emphasis is placed on this and therefore whatever happens after death is in God’s hands.

Life after Death

Judaism has always believed in eternal life with God after death but the details are varied and unclear and unlike other religions, no one view has ever been officially accepted.

The Rabbis taught that the body and soul cannot survive without each other. They explained that the soul leaves the body at death but that they are eventually reunited at the end of time in ‘the world to come’, with the body too being resurrected. Because of this, Orthodox Jews do not believe in cremation as this would interfere with this process. Progressive Jews do not believe in bodily resurrection and therefore cremation is accepted.

Reincarnation

Again there are a variety of views in Judaism as to whether the human soul is reborn within another body. Reincarnation is mainly regarded as a matter of speculation. It doesn’t have any effect on our moral, earthly life.

Summary

The marking of important life cycle events with symbolic rituals and traditional customs links us to our past and also our future. They serve to reinforce the central beliefs such as the Covenant, Commandments and Community, which define Judaism and Jewish life.